How Viable Are BitVM Based Pegs?

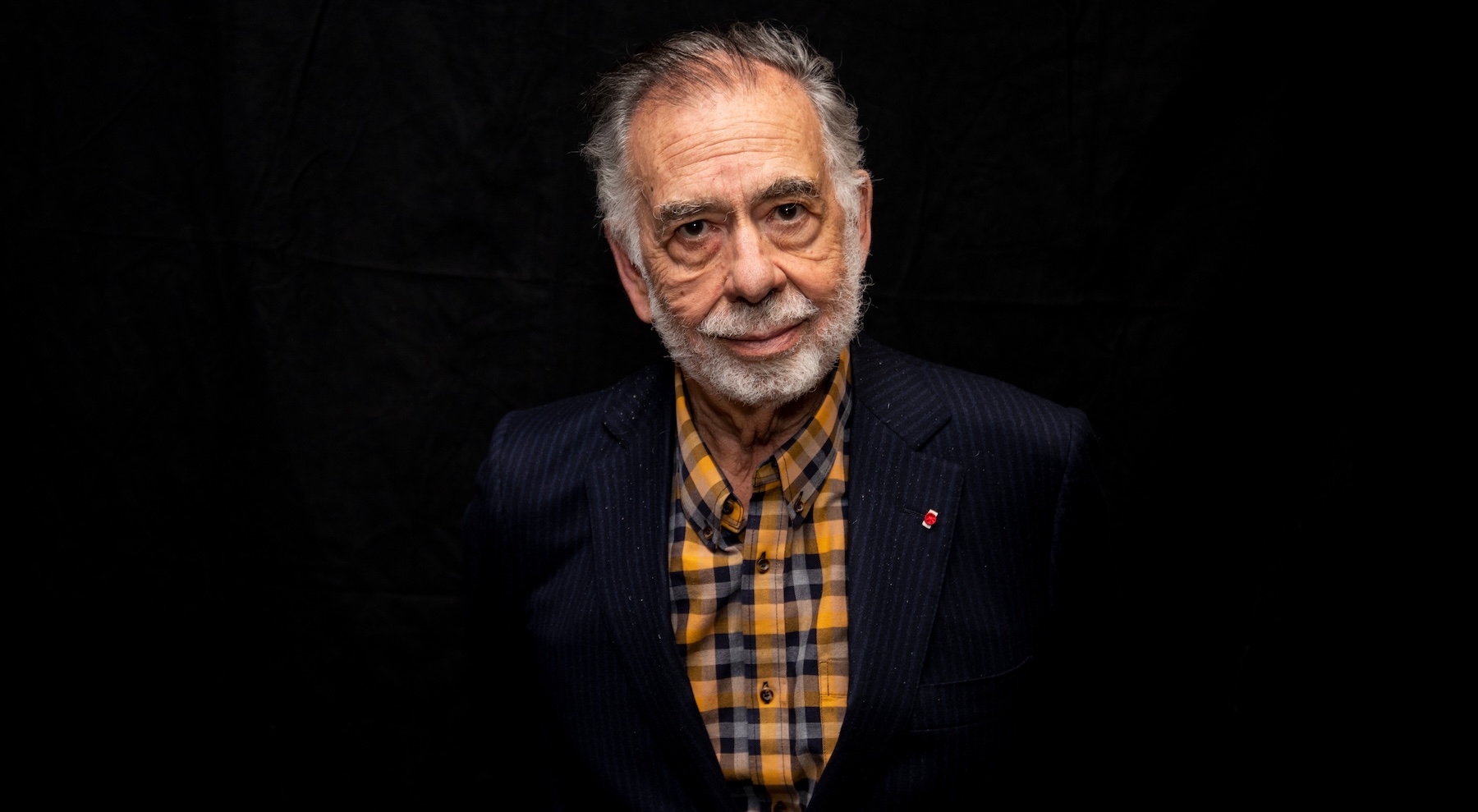

A look at a recent report by Galaxy looking at the economic viability of two way pegs secured by BitVM.

BitVM earlier this year came under fire due to the large liquidity requirements necessary in order for a rollup (or other system operator) to process withdrawals for the two way peg mechanisms being built using the BitVM design. Galaxy, an investor in Citrea, has performed an economic analysis looking at their assumptions regarding economic conditions necessary to make a BitVM based two way peg a sustainable operation.

For those unfamiliar, pegging into a BitVM system requires the operators to take custody of user funds in an n-of-n multisig, creating a set of pre-signed transactions allowing the operator facilitating withdrawals to claim funds back after a challenge period. The user is then issued backed tokens on the rollup or other second layer system.

Pegouts are slightly more complicated. The user must burn their funds on the second layer system, and then craft a Partially Signed Bitcoin Transaction (PSBT) paying them funds back out on the mainchain, minus a fee to the operator processing withdrawals. They can keep crafting new PSBTs paying the operator higher fees until the operator accepts. At this point the operator will take their own liquidity and pay out the user’s withdrawal.

The operator can then, after having processed withdrawals adding up to a deposited UTXO, initiate the withdrawal out of the BitVM system to make themselves whole. This includes a challenge-response period to protect against fraud, which Galaxy models as a 14 day window. During this time period anyone who can construct a fraud proof showing that the operator did not honestly honor the withdrawals of all users in that epoch can initiate the challenge. If the operator cannot produce a proof they correctly processed all withdrawals, then the connector input (a special transaction input that is required to use their pre-signed transactions) the operator uses to claim their funds back can be burned, locking them out of the ability to recuperate their funds.

Now that we’ve gotten through a mechanism refresher, let's look at what Galaxy modeled: the economic viability of operating such a peg.

There are a number of variables that must be considered when looking at whether this system can be operated profitably. Transaction fees, amount of liquidity available, but most importantly the opportunity cost of devoting capital to processing withdrawals from a BitVM peg. This last one is of critical importance in being able to source liquidity to manage the peg in the first place. If liquidity providers (LPs) can earn more money doing something else with their money, then they are essentially losing money by using their capital to operate a BitVM system.

All of these factors have to be covered, profitably, by the aggregate of fees users will pay to peg out of the system for it to make sense to operate. I.e. to generate a profit. The two references for competing interest rates Galaxy looked at were Aave, a DeFi protocol operating on Ethereum, and OTC markets in Bitcoin.

Aave at the time of their report earned lenders approximately 1% interest on WBTC (Wrapped Bitcoin pegged into Ethereum) lent out. OTC lending on the other hand had rates as high as 7.6% compared to Aave. This shows a stark difference between the expected return on capital between DeFi users and institutional investors. Users of a BitVM system must generate revenue in excess of these interest rates in order to attract capital to the peg from these other systems.

By Galaxy’s projections, as long as LPs are targeting a 10% Annual Percentage Yield (APY), that should cost individual users -0.38% in a peg out transaction. The only wildcard variable, so to say, is the transaction fees that the operator has to pay during high fee environments. The users funds are already reclaimed using the operators liquidity instantly after initiating the pegout, while the operator has to wait the two week challenge period in order to claim back the fronted liquidity.

If fees were to spike in the meanwhile, this would eat into the operators profit margins when they eventually claim their funds back from the BitVM peg. However, in theory operators could simply wait until fees subside to initiate the challenge period and claim their funds back.

Overall the viability of a BitVM peg comes down to being able to generate a high enough yield on liquidity used to process withdrawals to attract the needed capital. To attract more institutional capital, these yields must be higher in order to compete with OTC markets.

The full Galaxy report can be read here.

What's Your Reaction?